The Repetition of China

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, China emerged in the European intellectual landscape not merely as a distant civilisation to be admired or exoticised, but as an irresistible philosophical question. Leibniz wrote that the Chinese “surpass us (though it is almost shameful to confess this) in practical philosophy, that is, in the precepts of ethics and politics adapted to the present life and use of mortals.”[i]

Furthermore, Leibniz explored the parallels between his binary arithmetic, the algebra of ones and zeros, and the hexagrammatic structure of the Yijing (I Ching), primarily through his correspondence with the Jesuit missionary Joachim Bouvet in the early 1700s. In his letter to Bouvet, Leibniz remarked that the connection between his binary arithmetic and the figure of Fuxi(伏羲), whom he described as the author of “one of the most ancient monuments of science found in the universe today,” revealed, in his view, “some influence of providence.” [ii] For Leibniz, this correspondence was not merely a striking coincidence but a profound confirmation of the universality of reason as a reflection of divine order. He interpreted the convergence between his own logical system and ancient Chinese cosmology as evidence that God’s rationality is inscribed across different cultures and epochs.

It was not only Leibniz, but also Samuel Johnson who recognised China as a mirror in which Europe might glimpse its own image, an image both familiar and estranging. In his comparative theological work Oriental Religions and Their Relation to Universal Religion: China, Johnson did not simply catalogue Chinese beliefs as exotic data for Western edification. Rather, he discerned in Chinese civilisation a profound spiritual and moral coherence that forced Europe to reflect on the limits of its own self-conception. He praised what he called “the Chinese creative faculty,” yet notably emphasised that its primary function was “to maintain and multiply; to reproduce, not to reconstruct.”[iii]

This was no trivial distinction: for Johnson, China’s genius lay not in revolutionary transformation, but in the ritual preservation of cosmic and social harmony. In this light, Chinese culture appeared as a countermodern model, less driven by progress and rupture than by continuity and ethical refinement. It offered a philosophical challenge to the European narrative of development, suggesting that civilisation might unfold not through invention alone, but through the deep repetition of foundational principles.

This view placed Johnson somewhere between Voltaire and Hegel, two towering figures of European thought who also turned to China as a philosophical foil, though in starkly different ways. For Voltaire, China served as a rational utopia governed by secular virtue and Confucian wisdom. He admired the empire’s meritocratic bureaucracy and ethical system as a rebuke to European monarchy and religious dogma. In his Essai sur les mœurs, he declared that the Chinese had perfected morality before we knew the meaning of it. Voltaire projected onto China a vision of Enlightenment reason purified of ecclesiastical authority, a secular model of governance founded on ethical self-discipline rather than divine revelation.

Hegel, by contrast, found in China the very antithesis of historical freedom. In his Lectures on the Philosophy of History, he famously dismissed Chinese society as trapped in a “patriarchal” stage of development, incapable of dialectical self-overcoming. For Hegel, the Chinese state was a massive unity without inner differentiation, where individuality was submerged under the weight of tradition and ritual. While Voltaire saw China as ethically advanced, Hegel relegated it to the infancy of Spirit, characterising it as stagnant, repetitive, and ultimately outside the actual unfolding of World History.

China as a Philosophical Question

These philosophical engagements demonstrate that the challenge China posed extended far beyond the realms of commerce, diplomacy, or missionary ambition. It struck at the very heart of the European mind, exposing the limits of its self-assured claims to universality, moral supremacy, and rational order. China became a persistent question that European thinkers could not avoid, precisely because it revealed an alternative path to the very ideals that the Enlightenment had begun to champion: reason, virtue, social harmony, and political legitimacy.

The Chinese example raised fundamental and disorienting questions. Could a society be virtuous without Christianity? Was divine revelation necessary for moral clarity? Might there be other, equally valid civilisational trajectories beyond the European model? These questions could not be ignored. China was not merely a point of comparison; it was a philosophical provocation, which revealed the fragility of Eurocentric certainties.

The questions that Europe asked about China in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have returned with renewed urgency in the twenty-first century. Then, as now, China appeared not merely as a distant civilisation to be studied, traded with, or converted, but as a fundamental philosophical contest. Today, however, China is no longer a puzzle confined to the European imagination. It has become a planetary question that confronts the entire world. Once seen as the exception to Europe’s teleological narratives of progress in moral, spiritual, and political terms, China now occupies a position that complicates the very foundations of modernity.

In the Enlightenment era, the question was how a civilisation untouched by Christian revelation could display such moral rectitude, bureaucratic efficiency, and cultural refinement. In other words, how a non-Christian empire could rival or even surpass Europe in ethical and political order. Voltaire admired Confucian rationalism as a secular moral framework for governance. Leibniz marvelled at China’s harmony maintained without metaphysical rupture. Johnson recognised in Chinese creativity a distinctive mode of reproduction: an artistry rooted in continuity, repetition, and the deep refinement of existing forms. The unspoken anxiety was that Christianity might not be the necessary foundation for civilisation after all.

In the present, the question has shifted but preserves the same structural logic. How has China, without embracing liberal democracy, achieved economic dynamism, technological ascendancy, and global influence that now surpass those of many Western states? The paradox is no longer primarily moral but political and economic. China appears to have fulfilled the logic of capitalist modernity more completely and more rigorously than the liberal nations that once assumed themselves to be its originators. In this sense, China remains Europe’s mirror. Yet the reflection it offers is more troubling. It reveals a possible future once imagined as uniquely Western: a world of accelerated productivity, pervasive surveillance, massive infrastructure, and state-directed global ambition, all without the liberal subject, without parliamentary plurality, and without the tenets of Enlightenment individualism.

What China reveals, once again, is the contingency of Western universals. Just as Enlightenment thinkers were forced to confront a civilisation that was moral without Christianity, we must now reckon with a state that is capitalist without Western democracy. The mirror has not disappeared. It has only grown clearer, sharper, and more difficult to ignore. Suppose modernism can be understood as the historical moment in which Europe encountered its own “unhappy consciousness” through the mirror of China. In that case, postmodernism signals a fundamental inversion of this reflective structure. In the modernist period, particularly during the Enlightenment, China served as a surface onto which Europe projected its fantasies, anxieties, and self-doubts.

Yet with the onset of postmodernity, this structure of reflection no longer holds. China no longer functions merely as a passive surface for European projection, but emerges as a subject in its own right, entering, reconfiguring, and in many ways subverting the system that once sought to contain it. The mirror turns, and in doing so, it is no longer positioned behind Europe as a static counterpart, but is placed in front, angled, recursive, and generative. What once served as a reflective surface for European self-examination now becomes an infinite mirror, proliferating images that are no longer stable reflections but shifting refractions.

China, no longer a philosophical antithesis or ethical exception, emerges as a world-making force that destabilises the inherited categories of global modernity from within. It refracts economic, technological, and ideological forms that elude assimilation into the West’s conceptual archive. In this infinite mirror, capital, power, and civilisational form appear not as derivatives of a European origin, but as divergent iterations, repetitions without return. What is reflected is not a single truth, but a dispersed field of perspectives, endlessly multiplied and estranged from their supposed source.

In this reversal, often referred to as postmodernity or, more precisely, countermodernity in Johnson’s sense, the concept can be rethought not merely as the fragmentation of the European subject or the collapse of its grand narratives. Rather than a condition of internal exhaustion or cultural relativism, it becomes the moment in which the West is subjected to a form of external recursion, mirrored and multiplied by a force it once positioned as its other. China, long regarded as a philosophical counterpart or civilisational curiosity, now assumes the role of Europe’s infinite recursivity: not its negation, but its echo extended through unfamiliar coordinates. What postmodernity reveals is not simply the implosion of Western teleology. Still, it’s an uncanny reflection, refracted through China’s appropriation, intensification, and redirection of the very instruments of modernity Europe once claimed as its own.

Rethinking Postmodernity

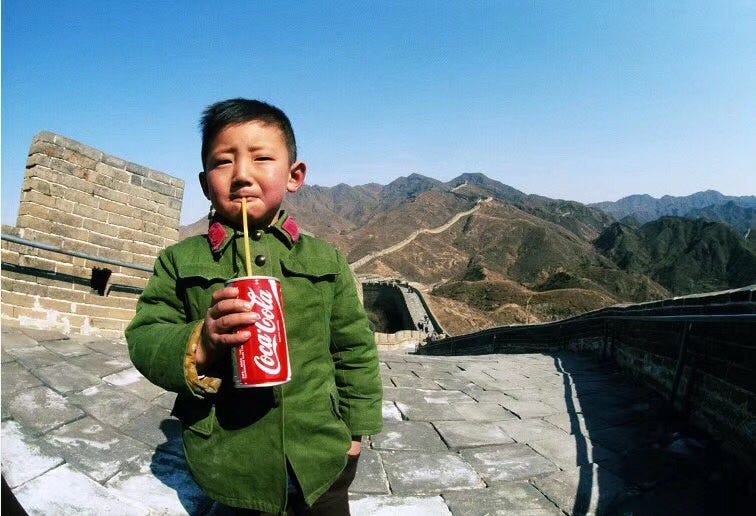

One piece of evidence supporting this hypothesis is the symbolism captured in the photograph “First Coke in Red China” (March 30, 1979), taken by American photographer James Andanson. Staged on the Great Wall in Beijing, the image depicts a Chinese boy drinking Coca-Cola, an iconic American brand, as China began to open its doors to global capitalism. This carefully orchestrated scene condenses the symbolic logic of postmodernity: history and ideology flattened into spectacle, the Great Wall transformed from a monument of sovereign isolation into the backdrop for consumer integration. Here, the East does not merely encounter the West; it completes its circuit. Coca-Cola, once a sign of American cultural hegemony, becomes a floating signifier in a world where ideology circulates without a centre. This dramatic scene, exemplified by Slavoj Žižek’s emblematic invocation of Coca-Cola, would come to shape the cultural and theoretical landscape of the 1990s. In this image, postmodernity reveals itself not as rupture, but as seamless absorption of contradiction into the global flow of signs.

In this moment, the East does not resist the West but completes its circuit. The red country, long imagined as the other of capitalist modernity, now stands embedded in its logistical core, assembling its goods and drinking in its signs. It is a scene not of contradiction but of recursive integration, in which the categories of producer and consumer, East and West, no longer hold. China, once imagined as modernity’s outside or philosophical other, now realises its most refined and operational form. The Coke bottle, once a metonym for Americanisation, no longer signifies the expansion of a particular culture but rather the condition of a world where signs, labour, and ideology circulate without a stable centre. In this configuration, postmodernity does not appear as fragmentation or irony, but as the seamless integration of contradiction itself.

In this sense, China becomes the mirror not of Europe’s past, but of its unresolved futures: generating permutations of capital, technology, and state power that retain the form of Western rationality while severing it from its Enlightenment origin. Postmodernity, viewed from this angle, is not a rupture with modernity, but its proliferation through an angled mirror, a recursive unfolding in which the West confronts its own logic, estranged, intensified, and returned from elsewhere. The mirror, once a metaphor for introspection and dialectical self-discovery, now becomes a dispositif of proliferation, an optical system without centre or origin. This is the vertigo of postmodern geopolitics: Europe, having once interrogated itself through the figure of China, now finds itself positioned within a hall of mirrors it cannot control, surrounded by images of its own displaced futures.

Global capitalism, in its current integrated form, would not have been possible without China. Far from existing on the margins of capitalist modernity, China has functioned as its engine room: the site where global value chains are materialised, where the abstractions of finance find concrete form through labour, logistics, and infrastructure. Since the late twentieth century, China’s integration into the world economy has not represented a deviation from capitalism’s logic, but rather its radical amplification. The unprecedented scale, speed, and precision of contemporary capital accumulation rely on the productive and administrative capacities that China has developed within its unique model of state-market integration.

In this context, the ongoing discourse of “decoupling” between China and the United States must be approached with caution. It does not signify a rupture between two distinct systems, but rather a readjustment within an interdependent architecture. What appears as decoupling is, as Foucault would suggest, a shift in governmentality, a new mode of managing the same relations of production and control under altered coordinates. China and the United States are no longer geopolitical rivals in the classical sense; they are co-architects of a planetary dispositif, whose operations depend not on liberal-democratic values but on predictive data, algorithmic governance, and logistical scalability.

Decoupling under these conditions is not a separation, but a rearrangement of protocols. The global capitalist system has already internalised China as a structural necessity, not as an external rival. Attempts to separate from China, whether through trade restrictions, technological embargoes, or industrial realignment, while simultaneously preserving the logic of global capitalism, are inherently contradictory. The infrastructures of capital, from chip production to rare earth extraction, from e-commerce platforms to AI model training, are no longer national but distributed across a system in which China plays an indispensable role.

This interdependence is especially evident in the domain of high technology, where no actor can claim full autonomy. Companies like DeepSeek, a leading Chinese AI developer, exemplify this entanglement. Despite their ambitions to achieve technological sovereignty, such firms remain dependent on foundational models, many of which are developed in the United States or trained using global infrastructure and datasets. The supply chains of advanced semiconductors, the architectures of large-scale machine learning, and the regulatory frameworks that govern AI ethics are all embedded in a complex matrix of transnational dependencies. In this context, technological development is less a matter of national autonomy than of navigating and negotiating an evolving assemblage of protocols, standards, and knowledge flows. What appears as innovation is thus deeply conditioned by pre-existing global architectures of power and computation.

In this light, China does not stand as a new or alternative civilisational model. Instead, it represents the most refined instantiation of Western capitalism to date. It has absorbed the core logics of European modernity—rationalisation, secularisation, and accumulation—and fused them with a centralised cybernetic system of governance. What distinguishes the Chinese model is not its rejection of class contradictions but its capacity to modulate, manage, and contain them within a tightly integrated apparatus of state power, technological infrastructure, and ideological scripting. Class antagonisms are not abolished; they are rendered legible and governable through real-time data feedback, social credit systems, and algorithmic surveillance. The Chinese state has thus operationalised the contradictions that liberal democracies continue to displace into political crisis.

China and Other Asias

China should not be understood as an alternative to European civilisation, but as its culmination. It completes the Enlightenment project in a form that Europe itself could neither sustain nor fully acknowledge. The dream of a rationally ordered, technologically optimised society, liberated from theological constraint and frictional pluralism, finds in China a disturbing realisation. The difference is not ontological but developmental. China is not the exception to capitalist modernity, but its telos: the convergence of market logic and state calculation, of logistical efficiency and social control, of cybernetic governance and imperial ambition. What emerges is not a new world but the perfected mirror of the one the West built, and perhaps no longer recognises.

In this regard, confronting the problem of China today demands more than an extension of existing critical theory; it requires a reinvention of radical thinking itself. The historical failure of socialism, particularly in its statist and developmentalist expressions, has left us with a depleted conceptual language for understanding China’s transformation. What began as a revolutionary project to overturn global capitalism has, in the Chinese case, culminated in the consolidation of a highly centralised capitalist state. The traditional categories of critique have been absorbed into a system that governs not merely through repression, but through infrastructural modulation, technical rationality, and administrative capture. In such a context, critique that repeats the assumptions of Western Marxism risks becoming complicit with the very system it seeks to challenge. The task now is not to restore a purer form of Marxism, but to acknowledge its exhaustion and open new pathways for radical thought outside its conceptual limitations.

This requires a perspective that moves beyond geopolitics and the linear historicism inherited from the Enlightenment and orthodox Marxist traditions. We must turn to a reflection on Asiatic modes of existence, not as cultural essence or identity, but as historically sedimented ways of being shaped by different relations to modernity, power, and time. These modes cannot be reduced to Western categories of progress or regression. They unfold in discontinuous rhythms and articulate forms of collective life that were only partially integrated into the capitalist world-system. To think through China today is to face a particular difficulty: a political formation that has internalised the legacy of Marxism while systematically foreclosing the emancipatory possibilities that Marxism once sought to activate. In place of revolutionary subjectivity, there is a population managed through logistical infrastructure and cybernetic control; in place of dialectical transformation, a system that integrates contradiction as a function of governance.

To understand this impasse, it is necessary to revisit the short twentieth century of Asia. This historical arc does not simply follow China’s revolutionary trajectory but marks a broader shift in which Asia began to march toward its own destiny. While China’s path, from the collapse of the Qing dynasty through the 1949 revolution to its accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001, has been central to regional and global transformations, it cannot be taken as the representative arc of Asia as a whole. Reinterpreting Wang Hui’s concept of the short twentieth century of China, it becomes clear that China’s historical experience must be distinguished from the complex and heterogeneous temporalities of the Asian region.

Across the continent, from the independence struggles of South and Southeast Asia to the postcolonial experiments and authoritarian consolidations in Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, and beyond, Asia’s twentieth century unfolded through divergent routes, shaped by local conditions and transnational entanglements. These trajectories were not derivative of China, but marked by their own internal logics and ruptures. To think the short twentieth century of Asia is thus to trace a multiplicity of beginnings, revolutionary, decolonial, and developmental, that refuse to be subsumed under the narrative of any single nation-state.

China may have resolved the contradictions of its revolutionary century by entering global capitalism, but historical tensions across the wider region remain unresolved. Decolonial projects were suspended, alternative modernities repressed, and political imaginations deferred. These divergent Asiatic modes of existence retain within them political and philosophical resources that have not yet been exhausted or thoroughly co-opted. They offer a basis for rethinking the limits of our categories and imagining other possible configurations of life beyond capitalist realism.

Engaging with these modes does not mean idealising them. It means recognising within them the persistence of other rhythms, practices, and struggles that dominant historical narratives have marginalised. The contemporary challenge facing China is not simply an economic or geopolitical issue, but a theoretical one. It demands that we question what becomes of critique when it is no longer grounded in the externality of class struggle, when revolution no longer serves as its horizon, and when the Marxist tradition itself has been folded into the mechanisms of state and capital. What remains is the imperative to invent: not a new system of theory or doctrine, but new concepts, new vocabularies, and new ways of thinking that can respond to the particular conjunctures of history we now inhabit.

[i] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Writings on China, translated and edited by Daniel J. Cook and Henry Rosemont Jr., Chicago and LaSalle: Open Court, 1994, pp. 46-47.

[ii] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, “Leibniz to Bouvet,” in Lloyd Strickland and Harry Lewis, Leibniz on Binary: The Invention of Computer Arithmetic, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2022, p. 180.

[iii] Samuel Johnson, Oriental Religions and Their Relation to Universal Religion: China, San Francisco: Chinese Materials Center Inc, 1978, pp. 6-7

.

Great piece. Thank you for sharing.

China is so civilized and wonderful with how much “sustainable development” they have accomplished! Just look at their green and renewable lithium mines.

Our Candian government is now following in their example in “sustainably open pit mining” the boreal forest so we can have AI powered self driving Elon musk cars for everyone , yay for civilization!

https://open.substack.com/pub/gavinmounsey/p/an-introduction-to-a-new-series-befriending?r=q2yay&utm_medium=ios

China clearcuts the mountain forests and replaces them with industrial solar panel farms. Just look at Taihang Mountain.

Who needs clean drinking water, fish or forests when we can have a technocratic high tech city paradise!

The Liqi River was once full of fish: Almost none are left. Chemical spills from the Ganzizhou Rongda lithium mine have killed many. “The whole river stank, and it was full of dead yaks and dead fish,” said one villager.: “Masses” of dead fish covered the river. The people got the mine shut down three times, only to have the government reopen it.

One of the elders in Tibet said, “Old people, we see the mines and we cry. What are the future generations going to do? How are they going to survive? ”. A local activist surveyed people in the area. Even if mining companies split the profits and promised to repair the land after the mines are exhausted, the Tibetans wanted no part of it. “God is in the mountains and the rivers, these are the places that spirits live,” he explained.” “sustainable development” technology (Lithium battery tech) offers everything: every luxury, every whim, available at the touch of a ‘carbon-free’ button. But the world that these technologies provide will be a rotting, desecrated, and, finally, dead world if we let them continue on their crusade to turn the living world into dead things, for profit and to perpetuate our obscene technologically addicted western “civilized society”.

In the concentrations extracted via industrial mining operations, lithium is harmful to living beings. It interferes with sperm viability, causes birth defects, memory problems, kidney failure, movement disorders, and so on. Other materials in an electric-car battery can be even more harmful than lithium, with nickel and cobalt electrodes being the most destructive component.

Isn’t sustainable development and “green” battery tech fun!

https://web.archive.org/web/20210216150810/https://tibetnature.net/en/lichu-river-poisoned-case-minyak-lhagang-lithium-mine-protest/